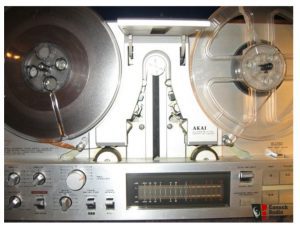

Akai made many quality reel to reel tape recorders from 1954 to 1985, and with the rare exception, Akai reel to reel tape recorders still work well today. As with many manufacturers, Akai made several all-tube machines, then moving into solid state units around the mid 1960s.

Akai had strong ties to the US companies Roberts (who also made reel to reel machines), and Rheem and Califone. The (sometimes confusing) history of Akai and Roberts can be found here..

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

And

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

As with many reel to reel manufacturers, I find that the technology matured and quality improved around 1973. While there are many ‘M’ and ‘X’ series Akai decks out there dating from the mid to late 1960s, many of these now need significant amounts of work to be reliable. In addition, as was typical for the era, the non GX series of Akai heads tended to be soft, and I’ve seen many non Akai glass heads being worn out due to use.

Roberts and Akai used the ‘dual lever’ mechanism for the transport, and many models of these decks were in production for over 10 years. Overall these decks were reliable, although some suffered from the cast metal cams cracking due to poor casting, locking up the transport, and rendering the deck useless. Fortunately, with the advent of 3D printing, the Reel Pro Sound Guys in Montana have made up a replacement kit for these cams, and they are available on eBay for a reasonable price.

The single motor Akai decks, such as the M and X series and the 4000 series did not generally suffer from motor failures as similar Sony decks did. Akai was an early adopter of three motor transports, where the reel motors were direct drive, as was the capstan motor. Decks as early as 1973 used direct drive motors, greatly simplifying the transport mechanics, and increasing overall reliability. Early Akai decks used relay logic for the transport, and later decks then switched to solid state logic with microprocessors to control the transport. Generally speaking, Akai transports were very reliable, and usually overbuilt, with a few exceptions.

Around 1973, Akai introduced the GX series of tape decks which used ‘glass heads’. As per their advertisements at the time, you could run an Akai GX series deck 24/7 for 17.5 years before they wore out. That’s 150,000 hours, as compared to a more typical 3000-4000 hour life span of steel heads. I personally purchased an Akai GX-630 in 1980 when I was in Grade 11. I was one of those people that used this reel to reel extensively, and I’d guess that I put a minimum of 2 hours a day on it for several years after purchase. I still have the deck, it still runs, and everything is still original on it. Akai was correct with their 150,000 hour claim. To date, while glass heads can fail, I have yet to replace a GX series head due to wear. They simply don’t wear.

We have, however, had the odd failure of Akai glass heads due to what we call ‘crystallization’. It seems to affect the earliest generation of glass heads (GX-260, etc, circa 1972) more than the later ones, however we have also seen two bad playback heads so far in the top of the line Akai GX747. We believe that the glass within the head develops hairline cracks. Other techs have said that some of the heads develop tiny pits in the surface of the head, causing poor tape to head contact.

Whether it’s the record head or playback head that’s affected by ‘crystallization’, the results are the same: Poor frequency response about 7Khz. The audio of the deck, even at 7 ½ ends up sounding very muffled. Finding good used replacement heads is tough for Akais, as no ‘standard’ steel heads fit, so you’re at the mercy of scrap decks sold on eBay for used heads. Fortunately, head failure is relatively rare on Akais.

Around 1979 or so, as cassette decks became more popular than reel to reel due to the low cost of tapes, Akai along with other manufacturers cut some corners in the construction of the tape decks. Some parts became plastic from the previously metal parts, and now, 40 years later, there are some reliability issues with these later decks.

The last Akai decks were the highly rated GX-747 that had models with and without dbx noise reduction, and the Akai GX-77 – a compact auto-reverse 6 head deck. The last Akai reel to reel was made in 1985. Akai diversified into musical instruments, and made many audio samplers. Akai went under in 2002, and the name was purchased by another company. I saw an Akai plasma TV around 2000 at the CES show, and it was terrible looking.

– Akai Pros and Cons –

| PROS |

Overall, the reliability was excellent. Most Akai decks were a sure bet when it came to reel to reels, with only a couple of lemons in the product line from the mid 1960s to the mid 1980s. (see ‘cons’ below)

Excellent frequency response. While not ruler flat, since the Akai GX heads don’t wear, the decks hold their frequency response very well. Many Akai decks come in for the typical servicing of noisy controls and switches, but a frequency response test shows that the calibration of the deck is still very accurate, despite not having been touched in 40+ years. There are very few other brands that can claim this.

Glass heads. These heads generally last the life of the deck, although I’ve seen a couple with open coil windings on one channel (very rare). I have also seen the record heads in a couple of decks not produce anything about 5Khz on both channels. While there is no visible indication that these heads were bad, my theory is that perhaps the glass structure cracks over time, causing the poor frequency response. This, however is highly unusual, as generally the Akai heads are excellent.

Simplified tape transport in later models due to the direct drive motors. Save for some bad feed-through solder connections on the transport logic boards, the Akai transports simply keep on going. Almost all Akai decks from around 1973 to 1985 are reliable, sound great, and are easy to maintain, making them a solid choice of a deck brand to purchase.

Lots of parts available. Since a ton of Akai decks were sold worldwide, and things like knobs interchanged between numerous models, most replacement parts are easy to find on eBay. This is the result of numerous Akai decks being parted out on a regular basis.

Long lasting rubber components. Akai’s rubber formulation for belts and pinch rollers did not suffer from the sticky goo mess that the Teacs and some Sony rubber did. While I do send some worn pinch rollers out to be refurbished, most Akai pinch rollers and belts are still in excellent shape despite being 40-50 years old.

| CONS |

Bad transistors. Akai used a transistor part number in many of their decks called the 2SC458. Almost all of these transistors were made by Hitachi, and for some reason, corrosion develops on the transistor leads over time. You can determine the 2SC458 transistors in an Akai deck without looking at the part numbers, as the wire leads are black instead of a shiny silver the way other transistors in the deck are. The theory is that this corrosion works itself into the silicone substrate of the transistor, causing noise, intermittent operation of a channel, and intermittent distortion. The rule of thumb is to immediately replace all 2SC458 transistors with a more modern day equivalent to eliminate these problems in Akai decks. I won’t sell an Akai deck without going in and changing all of these problematic transistors out. Almost every Akai deck made from 1973 to about 1980 had these 2SC 458 transistors in the preamp circuitry. The last models of Akai, the GX646, 747 and GX-77 did not use these transistors.

Bad cams, dual lever Akai models. Akai apparently had some bad castings of the cams found under the rotary levers on the transport, causing them to crumble. Fortunately, replacement parts are found on eBay or from www.reelprosoundguys.com in Montana. They have 3D printed up a kit to replace them, at well under $100 USD. We’ve installed a few of them, the skill set needed is moderate, and a good set of hand tools is all you need.

Sticky lithium grease. While most Akais did not suffer from the sticky white lithium grease found in many Teacs and Sony decks, some later Akai decks did use this grease as well, causing the transport to stick. This was especially the case for the tape tension levers of the Akai GX 635, to the top of the line GX-747, and the entire transport of the GX-77. (See ‘lemon’ writeup below). Removal of this grease in the tape tension levers is relatively easy to do, and is considered a minor repair.

Bad glass heads.

As stated earlier, some Akai decks will develop frequency response issues within the glass heads, resulting in almost no frequency response above 7Khz. Finding Akai heads is tough, as no other brand of head will fit an Akai deck without some serious modifications. Fortunately, glass head failure is relatively rare.

| AKAI’S LEMONS |

Akai made many very reliable tape decks throughout their manufacturing run, but I need to single out 3 decks that are problematic, and why.

Akai GX-400 and 400-DSS. These were early 1970s top of the line decks in either stereo, ½ track or quadraphonic models. The deck design has a couple of limitations. First, there is only one record and playback level control for all 3 speeds, which results in a tech dialing in the deck for optimum performance on one speed, and hoping the other two are close in spec (they usually are).

The GX-400 series specifically has three distinct issues:

Slow REW and FF at the end of the tape. Out of the 20 or so GX 400s we’ve had through here in the last 5 years, only about 4 of them have had enough reel motor torque to properly rewind or FF the tape all the way through. Most decks would slow down towards the end of the tape, and while only one deck needed manual assistance to get to the end of the tape, we’ve never been able to figure out what is causing this slow speed at the end of the tape. It’s either a bit too much tape path friction, despite cleaning the tape path, or there may be a borderline flaw in the reel motors. If you’re looking at buying one of these decks, expect REW and FF to be slow.

Cracked module connectors. The Akai 400 series has several 22 pin PC board edge connectors that connect the record, play, and transport PC boards to the chassis. We’ve had several of these decks come in where the female portion of the edge connector splits at the ends, causing bad or no contact with the PC boards, resulting in intermittent or no audio. While these edge connectors are available, changing them out with 22 wires on each one is a daunting task, and takes several hours to do.

Broken tape tension arm. This is the fatal flaw of many 400 series decks. The right-most tape tension lever has a plastic (nylon?) threaded insert that the tension lever bolts to. Due to the original material used, along with heat and vibration, the plastic insert cracks and breaks, ending up with the tension arm falling below its normal rest position. Sometimes this tension is then lost, and that arm is unique to the GX400 series. Nothing else will fit from the Akai line. Worse, the auto reverse sensing connection runs through the middle of that plastic shaft, so that ceases to function as well.

There was a fellow selling 3D printed nylon shafts and replacement tension arms, but priced at well over $300 USD each! I also haven’t seen them listed on eBay in a few years. We are currently experimenting with 3D printed shafts that look promising so far. If you see an Akai GX-400 with a missing tension lever, the deck is worth very little money until someone clones that tension arm.

Akai GX-77. Stay away! This was Akai’s last, and top of the line auto reverse 7” deck with 6 heads. Looks-wise, it was great, with a flip down head cover, and audio quality to die for.. when the deck works. Engineering-wise, the thing is a disaster for a few reasons.

Brittle plastic parts. The whole self-loading mechanism is a nightmare to service, and we’re seeing some of the crucial cam gears crack due to age. Unfortunately, replacement parts are slim to none for these units.

White lithium grease. This grease that hardens over time is found throughout the transport, and once it gets hard, it’s a 4-5 hour job to pull the transport apart to clean all the gunk out. It can be done however, but it is expensive. See a separate article here on this website regarding this.

Underrated capstan motor. This is the big one, since it’s a servo motor unique to the GX-77. The transport uses a dual capstan shaft design, with one really long belt between the capstan motor and the flywheels. We’ve had in many GX-77s in the last few years that would play one side of the tape just fine, then the deck would slow down over about a 5 minute period, and stop completely. Let the deck cool down, and the cycle would repeat.

After many hours of playing with a number of these defective decks, we’ve come up with the following theory as to why the motor fails. We noted that the time it would take the capstan flywheels and motor to stop spinning at power-down ranged anywhere from 4 seconds for a problematic deck, to about 6-7 seconds on a deck that worked. We therefore tore down the entire transport, and cleaned and lubricated the capstan flywheel sleeve bearings, and usually noticed a decrease in friction of the flywheels, putting less of a load on the capstan motor.

The capstan motor also has a thermistor in line with the motor supply voltage, preventing burnout of the motor if it gets jammed. Our theory however is that as the friction of the capstan flywheels increases over time, the motor is subjected to a slowly increasing load, which eventually causes shorted motor windings. The shorted motor windings draw more current as the motor gets warm, causing the thermistor to heat up and limit the current going to the motor, resulting in motor slowdown and the eventual stopping of it. Turn the deck off for ½ hour, the motor cools off, the thermistor cools down, and the deck works fine again.

Since the capstan motor is a servo unit with a controller PC board, it’s unique to the GX-77 and no other motor will fit. If you’re lucky and can find a used motor on eBay, they appear to be selling for about $100. Given all of the other problems with the GX-77, we caution you not to put a lot of money into this problematic, over-engineered deck.

Update: Since the original writing condemning the Akai GX-77, we’ve overhauled and sold a number of them, with none coming back. All of the problems stated above are indeed true for the GX-77, however if properly serviced, they can still work great. When dialed in, they can run flat to 22Khz, relatively unheard of for a consumer 7” deck. The key for a long life GX-77 is to run it every month. While we tell all of our clients this, some people pick up decks from us and run it for one tape, then store the deck for 2 years, and then the deck has problems with it. Reel to reels are like vintage cars.. keep driving them to keep things moving and lubricated!

GX-747. The highly coveted Akai GX-747 goes for large amounts of money, especially the black version with built in dbx. When working, the 747 is an amazing deck. It however, suffers from two problems:

Motorized tape tension levers. There are two tiny motors attached to each of the tension arms, which retract the arms to a ‘rest’ position when you first turn the deck on with no tape on it. There are two even tinier belts (1.9”) that connect the motors to the small gear assembly driving the tension levers. If the belts stretch even a little bit, the tension arms will cycle back and forth. They never go to the rest position, as the gears don’t have the torque to get them there. While it’s not hard to change the belts, the tape tension levers also suffer from sticky white lithium grease, which also puts additional stress on those belts. Disassembling the tension levers is a bit tricky, and beware trying to find any parts if you happen to break the assembly in any way when you pull it apart.

Lack of available parts for the 747. Since these decks command a premium price, and not many were sold compared to other models of Akai, finding parts is very difficult for the 747. This is especially the case with cosmetic pieces, and things like the CPU processor (which rarely fail). Break the swing-open door covering the controls, and you likely will never find a replacement.

While the 747s are a great deck, you can achieve the same performance from the less expensive and more readily available Akai GX 635, 636, and 646.

Overall, almost all Akais offer reliability and great performance from their glass head models, and are generally a good bet to consider as a moderate to high end consumer reel to reel tape deck.